Videos of Jews who have converted to Christianity have been emerging on the internet. There seems to be a common thread among many of them: they were taught at an early age that the New Testament was an evil book and they should stay away from it. I don’t even blame them for thinking Christianity is evil; just look at the atrocities committed against the Jews in the name of replacement theology. But, I don’t think that Jews, nor Christians for that matter, should avoid reading something on the account of it being heresy. As a minimum, we need to be prepared to give an answer to objectors and we need to hear the objection before we can respond.

[Read More]

Hermeneutics

Faith, Believe, Fides, Credo, and Gelēfan

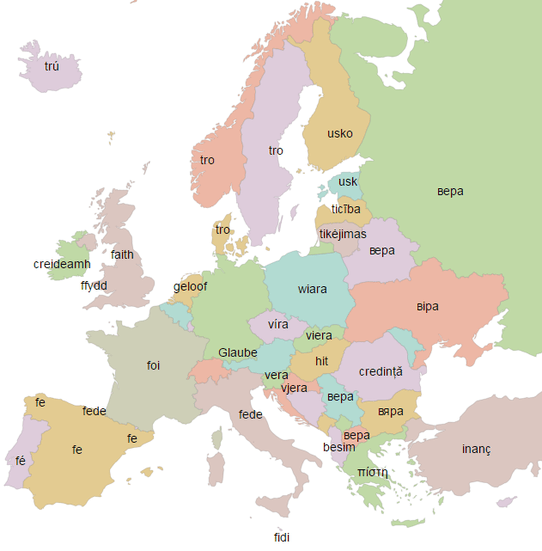

The way we speak affects the way we think and the way we think affects the way we speak. And the way we speak is affected by centuries of geopolitical conflict and linguistic changes. Check out this map with translations of the word, “faith,” in various languages around Europe:

If you look at the map, you can see certain words that are similar and clumped together. The Slavic languages have something like “vera” (in the Cyrillic alphabet, “вера”). Icelandic, Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish are all from the North Germanic branch, so they are all similar, whereas German and Dutch are from the West Germanic branch, so they look like each other.

[Read More]

Nuances in English translations of John 3:16

One of my favorite authors calls John 3:16 the most beautiful 25 words of the English language and I agree. The book he wrote was translated into Russian, where John 3:16 only occupies 21 words (not to mention that the original Greek is actually 26 words). When the book was translated into Russian, it maintained the figure of 25 words. It was a good translation, but sometimes when we explain the Gospel, we need to use localization.

[Read More]

What is an Inclusio?

Inclusio is just another word for sandwich.

-John Niemelä

Ancient Greek and Hebrew literature, such as the Bible, did not have punctuation and paragraph breaks, so the authors had to use other methods to tell their audiences when certain things were happening in the structure of their books. One literary device they used to do this is called the “inclusio.”

[Read More]

A Chiasm Noticed

A lot of details stand out when you read the Bible in its original languages. I’ve been reading through James lately, which is a book that has suffered greatly at the hands of English translation (especially toward the end of chapter 2).

I came across a noticeable turning point in Jas 4:6b-7a this morning:

”God opposes the proud, but gives grace to the humble.” Submit yourselves therefore to God. Resist the devil, and he will flee from you. (ESV)

It would be easy to breeze through this in English and take away something beneficial. But, if we take a look at the Greek, we might notice what we call a “chiastic” structure:

MosaicLawopoly

Everyone who loves Monopoly has his own set of house rules (Greek οἰκονομία …hehehe). I’m not going to talk about American politics today, but I saw the picture above on facebook that’s a jab at Bernie Sanders, and I wanted to turn it into something Bible-related. Whoever made the Bernopoly post must have been anti-Bernie, but someone from a pro-Bernie point of view made a similar post:

Well, I’m not going to ramble on about which Monopoly board I like better, but I would like to jump on the bandwagon and use Monopoly to explain economics. More specifically, I want to try to explain how economics worked in Israel during the Mosaic Law using an overly simplified Monopoly illustration… and will probably fail miserably.

Here it goes:

Rules of MosaicLawopoly

The game starts with all of the properties distributed evenly among all players except for one, who’s not allowed to have property. Players can buy and sell properties from each other, but after 50 laps around the board, the properties get redistributed as they were at the beginning of the game.

[Read More]